burt goldberg history

.pdf

Steve Paxton's "Goldberg Variations" and the Angel of History

Author(s): Ramsay Burt

Source: TDR (1988-), Vol. 46, No. 4 (Winter, 2002), pp. 46-64

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146977

Accessed: 11/11/2008 08:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to TDR (1988-).

http://www.jstor.org

|

Steve |

Paxton's |

|

|

Goldberg |

Variations |

and |

||

the |

Angel |

of |

History |

|

RamsayBurt

Ann Daly hasrecently observed that:"The fundamentalirony of dance history

is that the dancesthat get inscribed-on |

celluloid, on magnetic tape,on paper- |

are the ones that become real" (2000: |

92). The paradoxis, of course, that such |

inscription translatesdances into a medium other than the one in which they were originally produced and thus surelymakes them less ratherthan more real.

Yet without such inscription are they not in danger of disappearingaltogether? It is againstthe threat of such disappearancesthat dance historiansstrive to put onto paper what they feel is important about aspects of choreographyand performance. This task is, I suggest, analogous to that of WalterBenjamin's "angel of history" (I970). His wings spreadand his mouth open, he staresfixedly, con-

templatingsomething, although he seems about to move on; this, Benjaminsays, is how one pictures the angel of history.

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events,

he sees one single catastrophewhich keeps piling wreckage upon wreck- age and hurlsit in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay,awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.But a storm is blowing from Paradise;it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows sky- wards. This storm is what we call progress.(Benjamin 1970:259-60)

The angel of history thus has three useful characteristics:he can savethe past, he is innocent, and he sees the past whole because he doesn't seek chains of events

with which to explain the present. In my perhapsarrogantattemptto assumethis angel's role-one which as I will explain cannot succeed-the wreckage that I

want to |

try and save from the catastropheof loss and deterioration is Steve |

|||||||||

Paxton's |

|

VariationsThis. is the name Paxton |

gave |

to an |

improvised |

dance |

||||

|

|

Goldberg |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

he performed between 1986 and 1992' |

to the pianist Glenn Gould's two cele- |

|||||||||

brated |

recordings |

The |

|

Variations Bach. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Goldberg |

by |

|

|

|

|

|||

The Drama Review 46, 4 (T176), |

Winter2002. Copyright? 2002 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

New York University and the MassachusettsInstitute of Technology |

|

|

|

|

||||||

46

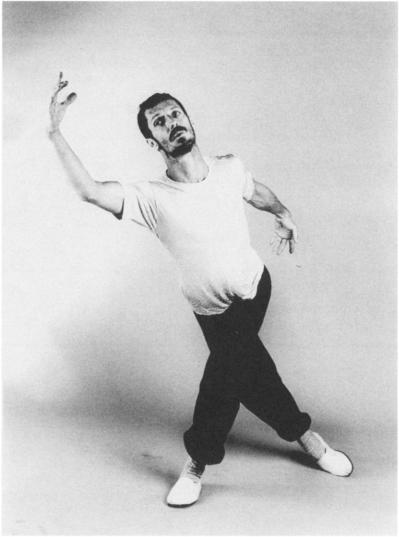

StevePaxton 47

dio in 1986.Noticehowthe

inevitablymakethearmas-

sumea ballet-like shape.

(Photoby LesleyHowling)

Steve Paxton is undoubtedly one of the most important dance artistsof the past40 years.However, while GoldbergVariationswas a very popularpiece in the late 198os and early I99os, and was performednearly200 times, virtuallynothing has been written about it. At the beginning of the 2Ist century it is relatively easy to find out about Paxton's work in the I96os and about his role in the development of contact improvisationin the 1970s, but much more difficult to learn anything about his work as a performer during the past 30 years. I saw

Paxton |

|

|

Variations |

couple |

of times in |

England |

in |

I986. |

I have |

||

|

|

perform Goldberg |

|

|

|

|

|||||

always |

loved |

Bach, |

but had never heard of The |

|

Variationsnor of |

Glenn |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Goldberg |

|

|

|

|||

Gould. Yearslater, on impulse, I bought myselfa CD of Gould's 1981 recording

of the Variations. |

to this |

prompted |

me to |

try |

to remember |

something |

Listening |

|

|

|

about Paxton's dance, and this led me to look for reviews to remind me about what I was convinced had been an important event. To my surprise,at first I couldn't find any-though I laterfound two. By chance, in a dancevideotheque

in |

Lyons, |

I came acrossa video |

recording |

of Paxton's |

Variationsfilmed |

|

|

|

Goldberg |

48 RamsayBurt

by WalterVerdin.2And then Paxton generously allowed me to record an interview in February2001 about this piece that he had firststartedto dance and that I had seen 15 years earlier.3

After 15 years our memories-Paxton's and mine-of this piece have inevi- tably sufferedloss and deterioration. I could have tried to obtain a copy of the

video and studied it exhaustively,or even askedif Paxton would look at it with me and talk about the piece. But then we would have probablyended up talking about the video ratherthanthe live performance.The difficultyof acknowledging the liveness and uniqueness of the performance event itself is one of the main

problems |

dance writers have. The fact that |

Variationswas an |

improvised |

|

Goldberg |

piece appearsto have made it more difficult to discussthan a performanceof set choreography,and this is surely one reasonwhy so little has been written about it. In this article I hope to show that GoldbergVariationscan help us imagine another way of writing about performance that acknowledges the value of all those qualitieswithin dance performancesthat cannot be fixed and aregradually

destroyedthrough |

rehearsal; |

without these |

very qualities,per- |

yet, paradoxically, |

|||

formance could not exist.

[T]he fetishization of the traces of lost dances and, as Peggy Phelan has observed, the act of writing about performances, irrevocably changes and distorts them.

In Benjamin'sparable,the storm that is blowing from Paradisestops the angel from making whole that which hasbeen smashed,and preventshim from bring- ing it back to life. Writing about performanceis similarlyinhibited in ways that do not affect writing about painting or literature.Readers of the latter usually

have the possibility of referringto the work under discussion, independently of what has been written about it. The newspaper critic writing a review on the night of the performanceand the historianwriting about performancesof Goldberg Variations5 years after the performance are both compelled to describe something that no longer exists, or that can only continue to exist outside the medium in which it was originally presented,in some alteredform-in writing, in photographs,films, costumes, designs, scores,but not as living, moving bodies in time and space. Dance critics and scholars are often amateursin the I8th- century sense, in that it is their love of dance that makes them attempt to be angels of history.But the fetishization of the tracesof lost dances and, as Peggy

Phelan has observed, the act of writing about performances,irrevocablychanges and distortsthem:

The urge to record has given rise to an odd situation in which some of the most radicaland troubling art of our culturalmoment has inspired some of the most conservative(and even reactionary)critical commentary. The desire to preserveand representthe performanceevent is a desire we should resist.For what one otherwise preservesis an illustratedcorpse, a pop-up anatomicalbody standingin for the thing that one wants to save,

the embodied performance. (1997:3)

Those who love dance should thereforebeware of killing the thing they love. When Michael Kirbywas editor of TheDramaReviewin the 1970s, he favored

an "objective" approachto descriptivewriting. Contrary to Phelan, he believed

StevePaxton 49

try and record the performance in words while

suppressingany subjectiveresponse or interpretationthat might distort the work itself. However, where dance is concerned, especially experimental dance, to write an objective description of largely nonverbal aspect of performance-of

the embodiment of subjectivity and its performance-is |

particularlydifficult. |

||||

Variationsis a work that |

explores aspects |

and |

qualities |

of embodied ex- |

|

Goldberg |

|

|

|||

perience which Western culturevaluesso little that it largelylacksthe vocabulary

to articulatethem. Because |

Variationssets out to |

explore |

those areasthat |

|

Goldberg |

|

evade verbalization,it is difficult to give a verbal description of the work itself. (Nevertheless, pragmatically,in this essay I will in due course try to describe GoldbergVariationsSally.)Banes has identified another problem with the "objec-

tive" approachto descriptivewriting. She argues:

[I]t doesn't provide a structurefor thinking about the work or for under- standingit. Certainly it is useful to future dance historiansor reconstructors to pile on the descriptivedetail. But, in terms of helping the contemporaryreaderunderstandthe work, it leaves one in suspense.

(I994:30)

Dance performancesdo not exist in a vacuum but engage in dialogue with other

discoursesand areasof |

Variations |

in |

dialogue |

with |

|

|

experience. Goldberg |

engaged |

|

|

|

J.S. Bach and Glenn Gould, and with the idea of variationand the problematics and paradoxesof live performancethat areraisedby Gould's recordingsof Bach's

VariationsPaxton's. |

performance |

needs to be seen within the wider con- |

Goldberg |

|

text of his careeras a whole, the work of his peers, and dance artistsfrom other generationswho have choreographedpieces to classicalrecitaland concert music in general and to Bach's music in particular.

The piece is also situated within a wider social and culturalcontext and this must include critical and scholarly writing about theatre dance and take into account the effects that Phelan warns us about. To discuss GoldbergVariations,it is necessaryto understandthe mechanismsthat enable the circulationof cultural forms. Art historians,by cataloguingworks of art,tracingtheir provenance-the history of their ownership since they left the artist'sstudio-and identifying key stylistic characteristicsof "old masters"serve the useful purpose, whether they intend this or not, of stabilizingthe art marketby establishinggroundson which a particularwork can be valued. A dominant type of dance history elaborates similarproceduresfor establishingvalue. These posit that the choreographer,as author and origin, is the source of authenticity and originality in the work by setting movement whose value manifests itself through unique stylistic charac- teristics.A rehearsaldirector,sometimes in conjunction with a notator,represents the choreographer'sinterestsby ensuring the dancers'faithfulnessto the original movement. Within this view, what the danceractuallydoes during the live per- formance itself may only be acknowledged as a representationof the original genius of the choreographeras this has been reproduced through a hierarchical

and authoritarian |

A work like |

Variationsshort-circuitsthis |

system |

system. |

|

Goldberg |

because it is improvisedand thus presentsa unique event that reproducesnothing and thus can have no value within the terms in which value is conventionally circulated.

Paxton presentedhis firstdance pieces atJudsonMemorial Church in the early I96os along with pieces by visual artists,filmmakers,and musicianswho were all interested in performance. This was at a time when some visual artistsin the

U.S., Europe, andJapanwere becoming interested in performance and the per- formative aspects of producing visual art, which offered possibilitiesfor freeing themselves from the art market. The extent to which the art market, public

50 Ramsay Burt

collections, and museums found it possible during this period to accommodate the "dematerialization"of the art object, as the critic Lucy Lippardcalled it (1973), is a matter of debate. However, it seems that what the economy of art works requires,asdo all economies, is not objectsbut the circumstancesof scarcity and lack through which to incite desire for possession. This is what critics and scholarsprovide by distinguishingbetween what is desirableand what is merely

mundane. Clement Greenberg played an important role in establishingJackson Pollock's reputation-and thereforedesirability-in the late 1940s and early'sos. JillJohnston playeda similarrole in drawingattention to the new dancepresented atJudson Memorial Church in the early I96os and then, to the surpriseof some of the dancers themselves, announcing the end of the Judson era in mid-I964 (Johnston I965).4 She was highly selective, singling out for particularattention Yvonne Rainer and one or two others within Judson Dance Theatre. Dance historians,from Sally Banes onward, have largelyfollowed Johnston's lead, concentratingon the same artistsand valuing their work for exemplifyinga formalist, minimalist aesthetic. What has been largely ignored is the fact that some of the dancers, influenced by minimalist and conceptual artists'interest in phenome- nology and in the ideasof Wittgenstein, performeda critique and deconstruction of the conventions surroundingperformance through an assertionof the physi- cality of the dancing body. By ignoring the radical,deconstructiveaspectsof the new dance of the I960s, dance history has inserted Paxton, together with the other dance artistswhose careers began with Judson Dance Theatre, into an economy that ensuresthe circulation of aesthetic value that is defined in a con- ventionally authoritarianway. Paradoxicallythis is an economy in which Paxton can be valued as a dance artistwhile the improvised dances he performs are, in effect, renderedvalueless.

In order to write about GoldbergVariations,an alternativeaccount of the place

of performance within the economy of representationis required. What this should explain is the way in which some performance, as Phelan puts it, "clogs the smooth machinery of reproductiverepresentationnecessaryto the circulation

of capital"(1993:148). Her answeris to see radical,experimentalperformanceas an instance of a libidinal economy, and the performance event as an excessive, ruinous squanderingof resourcesthat escapesthe cycle of circulationby terminating it.

In performance art spectatorshipthere is an element of consumption: there are no leftovers, the gazing spectatormust try to take everything in. Without a copy, live performanceplunges into visibility-in a maniacally chargedpresent-and disappearsinto memory, into the realm of invisibility and the unconscious where it eludes regulationand control. Performance resiststhe balanced circulationof finance. It savesnothing; it only

spends. (Phelan 1993:148)

In Phelan's opinion, because performance saves nothing and disappearsinto memory, it cannot effectively be described. But by pointing this out, Phelan in effect provides me with a definition of what I value about the experience of

watching improvisedperformances |

like |

Variations:the thrill of a |

height- |

|

Goldberg |

ened situationin which it is imperativeto takein asmuch aspossible;the intensity of a chargedpresent (though not alwaysa maniacalone) that exceeds and disrupts systemsof economic circulation.

Variationswas not, however, a destructiveor |

negative piece |

and while |

||

Goldberg |

|

|

|

|

it was undoubtedly radicalit was not |

iconoclastic. It was a |

piece |

that |

|

|

particularly |

|

|

|

exploited, with exceptional clarity,an extraordinarysensitivity that Paxton had worked hardto develop over a number of years. This sensitivityhas alwaysbeen directed toward the sources of movement within his body and the effects during

StevePaxton 51

performance of particularlysubtle nuances and seemingly insignificant events. Although GoldbergVariationswas not without some dark aspects, overall it was affirmativein ways that distinguishmost American postmodern dance from the more melancholy and bleak atmosphere that so often characterizedEuropean postmodern dance around that time. In its own terms, some sections of Goldberg Variationswere unashamedlyjoyful. But one of the most striking things about it was the confidence with which Paxton set out to explore premiseswhich were so differentfrom those thatwere conventionallyassumedto define aestheticvalue and the significance of dance performance. This was not an act of provocation but arose because Paxton seems to have seen possibilitieswithin these premises

that suggestednew sortsof experience beyond what was currentlyimagined. My aim in writing about this work is not to try to save this piece as a mummified fetish or an illustratedcorpse but, through a discussionof its premises,to identify these new possibilities.

While Paxton was dancing he sometimes listened for the traces of Gould's singing, which the recording engineers had not man- aged to excise.

Without an illustrated |

however, what I write about |

Variations |

corpse, |

|

Goldberg |

will only be meaningful for those who saw it and can remember more about it than I could before I found the notes I wrote in I986 and saw WalterVerdin's

video. Here then, supplemented by a review by MarciaSiegel and my interview

with Steve Paxton, are |

my |

memories of |

|

Variations. |

||||||

I saw |

|

|

|

|

Goldberg |

|

|

|

||

Variationstwice |

in |

1986. First, |

in |

April |

at |

Dartington College |

||||

|

Goldberg |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

of Arts during an annualInternationalDance Festival,Paxton performedthe first 15 of the 30 GoldbergVariationsThen. in late August I saw him perform all 30 variations at the ICA Theatre in London. At the start of both performances, Paxton introduced the piece wearing a T-shirt, loose black cotton trousers,and his signatureblack Chinese "kung-fu" slipperswith white cotton soles. He ex-

plained about Glenn Gould and his two recordingsof Bach's GoldbergVariations, the first made in I955 when he was 22 years old, the second in 1981 at the end of his career.Paxton said a little about Gould's eccentricities including the fact that he sometimes sang along while playing. While Paxton was dancinghe sometimes listened for the traces of Gould's singing which the recording engineers had not managed to excise. Paxton's tone was casualand pointed to his personal interest in this music and this particularrecorded performance of it. At the full performanceat the ICA he said that he was using the I981 recordingfor the first 15 variationsand the I955 one for the last 15. Paxton confirmed thathe invariably used them this way round so that he had the sprightly energy of the youthful Gould to help carry him through the later variations.

The |

Variationsconsist of an aria followed |

by 30 variationsand then a |

|

Goldberg |

repeat of the opening aria-32 sections in all. The ariabegan in a blackoutafter Paxton had left the stage. He didn't dance with it, returning toward the end of it with a white half-maskpainted onto his face that included his nose but left his

mustache clear. I remembered this mask as extremely glossy,and assumedthat it was grease paint. Paxton however told me that it was slightly green French clay,

which graduallydried out as the piece progressed,ending up by the conclusion

of the performance cracked and desiccated like a desert road. If not dancing to the aria gave Paxton the time he needed to put on his mask, it was also concep-

tually appropriatethat his variationsor improvisationsto Gould's performanceof Bach should startwith the first variation. Paxton sometimes performed all 30 of the GoldbergVariationswithout a break, as he did during a short season at the

52 Ramsay Burt

Kitchen in New York City in March 1987 when it was performed along with MO RE, a duet with LisaNelson using music by Robert Ashley.At the ICA, he performed the first 15 before the interval. When he returned, having changed into a clean T-shirt, he performed the rest of the variations, including some movement during the finalaria,but leaving the stagebefore the end of the music.5

Glenn Gould observed in his notes for the sleeve of the 1955 recording that afterthe "aloof carriageof the aria,"which Bach probablydidn't actuallycompose himself,6 the first variation comes as a "precipitous outburst" (in Page 1987:25). This is certainly how he played it. What is elaborated upon in each variationis not the melody of the ariabut its bassline, so that there is no obvious connection between aria and variations,hence the suddennesswith which the

first variation breaks out. Written in the last decade of his life, The Goldberg Variationsis almost the only example of variations in Bach's oeuvre (although variations were a popular form during the Baroque period), and consists of a

series of complex pieces of contrapuntalwriting. As a late work, The Goldberg Variationsmakes for much more complex and demanding listening than early pieces like the Airfor the G Stringwhich Doris Humphrey used to make a piece of the same name in 1928. WhereasAirfor the G Stringhas one extremely mem- orablemelodic line that is woven againsta slow, regularbassaccompaniment, the pleasure of listening to The GoldbergVariationsis in the complex way several differentmelodic lines combine or are played off againstone another. It includes

severalcanons, |

fugues, |

and |

In a |

fugue |

the theme is |

repeated |

in dif- |

|

|

passacaglias. |

|

|

ferent registers,by the left and right hands, one afterthe other, often overlapping in a continuous and increasinglycomplex way leading to a final resolution. In a

the theme is |

split |

into two voices that |

and |

seemingly |

passacaglia |

|

continuallyrepeat |

chase one another. Some of the variationsare quite short, some longer. Together with the aria,they are all in G majorexcept for three variationsin G minor, two of which are very slow and meditative. It was written for the harpsichordrather than the piano, and is full of trills and other baroque ornaments. Altogether the

speed |

and |

complexity |

of The |

Variationsallowed Gould to use them for |

|

|

Goldberg |

||

incredibly glittering displaysof pianisticvirtuosity. |

||||

The clarity and accuracy of Gould's daring playing and its lack of Romantic overlayare qualitiesthat also characterizePaxton's dancing. MarciaSiegel wrote that Paxton's movement was "totally unpredictable,working againstthe formal patterns of Bach by capturing the rhythmic thrust and often the logic of the musical line" (1987). I certainlyremember the way the movement capturedthe rhythm and logic of the music. In 1986 I recorded that during one variation Paxton's intricate footwork fitted the music so closely as it drew towards its conclusion and ended so deftly and exactly with the music that it raiseda laugh from the audience. But I suspect that what Siegel was getting at when she said

Paxton worked |

against |

the formal |

patterns |

of The |

Variationswas the fact |

|

|

|

Goldberg |

that there was a postmodernist sensibility informing his performance. Hum- phrey's Airfor the G Stringseems to be an almost inevitable choreographic re- sponse to one of Bach'sbest known pieces. It is perhapsthe fact that The Goldberg Variationswasn't particularlywell known that allowed Gould initially to use it as a vehicle for his own fascinating,idiosyncraticinterpretation.It is not therefore a piece of music that a choreographermight easily turn into a definitive musical visualization,but one which allows almost endlesspossibilitiesfor interpretation. Paxton picked and chose one voice or another from among the many voices and interactionsbetween voices, sometimes jumped between these, listened for

Gould's own half-erasedsinging, and at times worked from his own personal responseto the musicalflow-using all these as startingpoints for improvisation. The fact that he could pick and choose in this by no means irreverent way

suggested a pluralismand openness that is characteristicallypostmodern. While

StevePaxton 53

Humphrey'spiece seemed to suggestthere was only one, definitiveway of setting movement to a particularpiece of music, Paxton, by the fact of improvising, implied that there was not one definitive way of dancingto TheGoldbergVariations but seemingly endless possibilities, and along with these, new and imaginative ways of hearing and experiencing Bach's music. Almost everything about the performance-the clothes, the casualintroduction, and above all the movement

to create this openness.

The factthat[Paxton]couldpickandchoosein thisby no means

irreverent |

a |

and |

thatis char- |

way suggested |

pluralism |

openness |

|

acteristicallypostmodern.

What I remember of Paxton's movement style in 1986 is surprisinglysimilar to Sally Banes's description of a solo improvisationby Paxton in the late I970s. She wrote:

There is a curious mixture of tension and relaxationin Paxton's body

when he dances. At times one sees analoguesto Cunningham's shapes, but more fluid, loosened: nimble, intricate footwork executed with floppy

ankles and feet; circularshapesmade with lax ratherthan held arms. (1980:69-70)

In |

VariationsI |

clearlyremember a similarmixture of control and fluid |

|

Goldberg |

ease. Precise, very small, almost isolated rotations of the head, or a subtle, deep twist within the muscles of an arm occurred within passagesthat seemed casually

exploratory.As an improviserPaxton was trying out preciselyfocused movement events yet with an openness to see where they would lead. Where Banes in the

late 1970ssaw lax ratherthan held arms,in I986 I saw much more extension and

projection within the arms;and where Banes had seen tracesof Cunningham, I saw tracesof ballet. These were not straightquotations but seemed to have been

digested and absorbedinto Paxton'svery personalmovement vocabulary.Paxton confirmed that he was conscious of these ballet associationsin his work with

GoldbergVariations,and I will return to this. In 1986 I kept seeing these tracesof ballet in the way Paxton extended his arms, upward or out to the sides, and in my notes I likened some of the statuesque poses he momentarily took up to

baroque figuresof the crucifixion-in |

El Greco. I |

may |

have made this |

|

particular |

|

connection through associationsof the music, but it must also have been due to

the lighting-sometimes merely a pool of downward light in the middle of the space surroundedby darkness.Paxton sometimes seemed to be looking upward to the light as if toward heaven, like a figure in a Baroque religious painting.

Siegel noted in GoldbergVariationsthat "he can burst into ecstatic whipping, fracturedturns, or melt into impossible twisted falls" (1987). Banes described

Paxton in the late 1970s as using the weight of his head or bent leg "to jerk his

entire body around the vertical axis with sudden violence" (1980:I87). In my notes from 1986 I recorded a great deal of turning, but I remember these not as

jerking and violent but as powerful movements initiated within the torso itself. I remember one variationin particular,which I think was the short "Variation

8." Gould plays this fast and |

and Paxton danced it |

entirely |

as an |

|

breathlessly, |

|

|

unbroken series of variationson turning, twisting, and rolling-a |

simple, head- |

||

long circling rush without hesitation from startto finish. Another I remember is

54 RamsayBurt

"Variation 13," whose light clusters of demi-semi-quavers Gould plays in an extraordinarilydelicate and almost hesitant way. During this, Paxton just wandered almostvacantlyaroundthe performancespace,with occasionalnods of the head or shrugsof the shoulderwhile he looked aroundwith a wide focus. Keep- ing a level of interest going in this way, he occasionallyseemed to try something but never let it take off. For example he extended one arm out behind him,

rotatinghis palm to face alternatelyup or down, and used it to tentativelyexplore space to his rear.Always appearing about to start something but never getting beyond that point createdan effect that seemed to complement and amplifythe

exquisite atmosphereGould had generatedthrough his interpretationof the mu-

sic. |

Siegel |

was |

perhapsthinking |

of a moment like this in |

Variationswhen |

|

|

|

Goldberg |

she observed that: "Always a diffident performer, Paxton seems to be trying to detach himself entirely from his actions in Goldberg"(1987). I rememberboth of these sections very clearly from the Dartington and London performancesand found them againin Verdin'svideo. When I discussedthis with Paxton and asked

whether there had been an underlying plan to his improvisationduring Goldberg Variations,he said emphaticallyno. He insisted that, if there were the similarities between differentperformancesof the samevariationsthatI believed I hadfound, he himself had neither been awareof them nor intended them: "If I were trying to reproduce the same improvised material in each of those variations,remembering the right sensationsfor each variation, that would be a phenomenal feat of memory." His concerns were precisely the opposite. Towardthe end of the six-year period during which he danced GoldbergVariations,he felt it started moving toward choreography.This, he says,was why he eventuallyfinishedper-

forming it.

Nevertheless Paxton remembers that there were some variations when he tended to turn and that the turns were eccentric:

The spine was not just a straightrod in the center of the turning but was actuallymoving itself inside the body while the body turned. I know I did that quite a lot and I loved to do that. I've stopped doing that since I

left |

behind because I do identify it with that |

period. Maybe |

it |

|

Goldberg |

|

did come up with the same variation. I think of those as based on breathing. There's one that's definitely laughing. The rhythmsare that and the pitch is bubbly-if you engage them in the body you feel a real lightness of being.

The rhythmof "Variation8" could be likened to laughter.Whichevervariation it may have been, Paxton says it was this particularvariation that got him "involved in feeling the music physically."He also remembers some very sloweddown variations that Gould played as if there were spaces between the notes:

"something like lights winking in the darkness,as if there were something dark between the notes forme [...] maybenot lightsbut pointsin the darkness,in velvety,

humid space" (200I). As well as "Variation 13" there are other slow variations in

Gould's recordingthat might also createthis image,just as there are severalother variationsthat doubtless also inspiredPaxton'sjoyful turnings.

When I askedwhether it wasjust the fact that Bach was a Baroque composer that made me see ballet armsand shouldersin some of the movements in Goldberg Variations,Paxton told me that by twisting the spine and torso in particularways it seemed inevitable that his arm should appearto be making a ballet "line."But he also revealed that he had started doing ballet exercises while listening to Gould's recording of The GoldbergVariationsand that this had led to his first performance of them in Santa Fe, New Mexico,

been in a depressionand found that his posture had become slightly bent over.