- •Introduction

- •List of tables

- •List of figures

- •Table of cases

- •Table of statutes

- •Glossary

- •1 UK construction sector context

- •1.1 The nature of the sector

- •1.2 The nature of professionalism in construction

- •1.3 The nature of projects

- •1.4 Procurement methods

- •2 Roles and relationships

- •2.1 Common problems

- •2.2 Client roles

- •2.3 Consultant roles

- •2.4 Professional services agreements

- •2.5 Architect

- •2.6 Quantity surveyor

- •2.7 Typical terms in professional services agreements

- •2.8 Integrated documentation

- •3 General contracting

- •3.1 Background

- •3.2 Use of general contracting

- •3.3 Basic characteristics

- •3.4 Risk in general contracting

- •3.5 Standardized approaches to general contracting

- •4 Design-build

- •4.1 Background

- •4.2 Features of DB contracts

- •4.3 Use of the JCT design build form (JCT DB 11)

- •4.4 Characteristics of JCT DB 11

- •4.5 Risk in DB

- •4.6 Approaches to DB

- •5 Construction management

- •5.1 Background

- •5.2 Use of construction management contracts

- •5.3 Principles of CM contracting

- •5.4 Overview of JCT CM Contract

- •5.5 Allocation of risk in construction management

- •5.6 Approaches to construction management

- •6 Collaborative contracting

- •6.1 Background

- •6.2 Use of collaborative contracting

- •6.3 Principles of collaborative contracting

- •6.4 Characteristics of collaborative contracting

- •6.5 Risk in collaborative contracting

- •6.6 Approaches to collaborative contracting

- •7 Risk allocation and procurement decisions

- •7.1 Types of risk in construction contracts

- •7.2 Dealing with risk

- •7.3 Procurement

- •7.4 Identifying and choosing procurement methods

- •7.5 Characteristics of procurement methods

- •8 Contract choice

- •8.1 Use of standard contracts

- •8.2 Contract drafting

- •8.3 JCT contracts

- •8.5 The burgeoning landscape of standard forms

- •9 Tendering and contract formation

- •9.1 The meaning of construction contracts

- •9.2 The formation of contracts by agreement

- •9.3 Contracts made by tender

- •10 Liability in contract and tort

- •10.1 Express terms

- •10.2 Exemption clauses

- •10.3 Incorporation by reference

- •10.4 Implied terms

- •10.5 Liability in tort for negligence

- •11.1 Standard of work

- •11.2 Statutory obligations

- •11.4 Transfer of materials

- •12.1 Implied obligations

- •12.3 Responsibility for the contract administrator

- •12.4 Responsibility for site conditions

- •12.5 Health and safety

- •13 Responsibility for design

- •13.1 Design management

- •13.2 Design duties in law

- •13.3 Legal responsibility for design

- •14 Time

- •14.1 Commencement

- •14.2 Progress

- •14.3 Completion

- •14.5 Adjustments of time

- •15 Payment

- •15.2 The contract sum

- •15.3 Variations

- •15.4 Fluctuations

- •15.5 Retention money

- •16.1 Contract claims and damages

- •16.2 Grounds for contractual claims

- •16.3 Claims procedures

- •16.4 Quantification of claims

- •17 Insurance and bonds

- •17.1 Insurance

- •17.2 Bonds and guarantees

- •18 Role of the contract administrator

- •18.2 Contract administrator as independent certifier

- •19 Sub-contracts

- •19.3 The contractual chain

- •19.7 Collateral warranties

- •20 Financial remedies for breach of contract

- •20.1 General damages

- •20.2 Liquidated damages

- •20.3 Quantum meruit claims

- •21 Defective buildings and subsequent owners

- •21.1 Claims in negligence

- •21.2 Statutory protection

- •21.3 Alternative forms of legal protection

- •21.4 Assessment of damages

- •22 Suspension and termination of contracts

- •22.1 Suspension of work

- •22.2 Termination for breach at common law

- •22.3 Termination under JCT contracts

- •22.4 Termination under NEC contracts

- •22.5 Termination under FIDIC contracts

- •22.6 Termination of contract by frustration

- •23 Non-adversarial dispute resolution

- •23.1 Background to disputes

- •23.2 The nature of construction disputes

- •23.3 The role of the contract administrator

- •23.4 Methods of dispute resolution

- •24 Adversarial dispute resolution

- •24.1 Adjudication

- •24.2 Arbitration

- •24.3 Litigation

- •24.4 Arbitration or litigation?

- •References

- •Author index

- •Subject index

Risk allocation and procurement decisions 107

examples, and the buying decisions at every point in the supply chain creates many more different ways of structuring a procurement method.

7.4.3Exit strategies

In any commercial engagement, it is important to be clear about exit strategies. Each participant, especially the client, will enter into contractual arrangements with a clear view about how they will be concluded. Entering into a contract is not a decision for life. The exit strategy will be structured around the achievement of the basic objectives of the project. In some cases, there may also be an exit strategy in the case of extreme non-achievement. The termination of a contract may occur because one party feels that the other has not fulfilled obligations under the contract and legal action is to follow. It is the task of the project team to ensure that an atmosphere of partnership and negotiation prevent this adversarial eventuality from happening. Either way, whether through legal recourse, through the complete fulfilment of contractual obligations or simply through a desire to waive contractual rights and depart, exit strategies can be written in to the contractual documentation for a project.

One interesting exit strategy in commercial property leases relates to the tenant’s obligation to maintain the property. In coming to the end of the lease, there is a process of identifying dilapidations that have to be repaired by the tenant before handing the property back to the landlord. These repairs can be very expensive and a tenant who has not planned an exit strategy may be unpleasantly surprised by the extent of the financial obligation that is related to this.

Whatever the actual contractual arrangement is British Standards Institute (2011) make this suggestion in their guide to construction procurement:

To effect smooth transitions of responsibilities at the close of a contract, good record-keeping and clarity of rights (such as ownership of materials, insurance policies) should be implemented to help make the process more straightforward and give confidence to those who are taking over responsibilities.

The checklist given in the British Standard is a useful list of point to be taken into consideration at the end of a project, especially if the parties are interested in continuing business relationships.

7.5CHARACTERISTICS OF PROCUREMENT METHODS

Each procurement method has relative advantages and disadvantages in relation to specific factors. Not all of these factors are important in all construction projects, but where one or more of these factors is a priority, it may influence the choice of procurement method to the extent of challenging the basic, client priorities set out in Section 7.4.1. What follows is based upon the descriptions and assumptions underlying each method as outlined variously in Chapters 3–7, which have highlighted the key characteristics and circumstances for the use of each of the

108 Construction contracts

Least |

Most |

PBC

PFI

GC

DB

CM

Figure 7.3: Client’s relative level of involvement

procurement methods. The most significant project characteristics that typify different procurement methods are:

Involvement of the client with the construction process.

Separation of design from management.

Reserving the client’s right to alter the specification.

Clarity of client’s contractual remedies.

Complexity of the project.

Speed from inception to completion.

Certainty of price.

The next seven Sections discuss each of these criteria in turn, showing how each procurement method fares.

7.5.1Involvement of the client

As set out in Section 7.4.1, the first question to consider is the extent to which the client wishes to be involved with the process. Some clients would wish to be centrally involved on a day-to-day basis and to fund the project as it progresses, whereas others might prefer simply to let the project team get on with it and pay for it when it is satisfactorily completed. There are many points between these extremes. The decision will depend, at least partly, on the client’s previous experience with the industry and on the responsiveness of the client’s organization.

Figure 7.3 indicates the extent to which each of the procurement methods relies on the involvement of the client. PBC enables clients to be disengaged from the construction process. PFI requires some engagement in terms of setting performance specifications and in organizing a complex and time-consuming tendering process. GC demands the client organizes not only the funding and tendering process, but also the overall control of the head contracts for design, construction, FM and operation, although it involves delegating most of the management functions to an architect or civil engineer. While it is not necessarily advisable, it is certainly possible for the project to be left in the hands of the team for its full duration. By comparison, DB does not involve a contract administrator in quite the same role. This places extra demand on the employer. CM removes the role of a main contractor completely and thus the client takes on the most active role. These relative levels of client involvement are summarized in Figure 7.3. The

Risk allocation and procurement decisions 109

Least |

Most |

PBC

PFI

GC

DB

CM

Figure 7.4: Separation of design from management

bars on the Figure are an indication of the range of levels for which each procurement method might prove suitable.

7.5.2Separation of design from management

The relationship between design and management was mentioned in Section 5.2.5. The principle that applies is the extent to which the design should form the basic unifying discipline of the project, or whether more quantifiable aspects should prevail. In the former case, it would be inadvisable to remove management from the traditional purview of the design leader. Such a distinction may emasculate the architectural processes and reduce it to mere ornamentation. But this is not always the case: not all projects are architectural. There is a marked difference between the contracting methods in this respect, as shown in Figure 7.4. However, when it comes to the use of PBC and PFI, the position is not so clear-cut. Whether the project is design-led or management-led is not dictated by the use of PBC, since a developer has a free choice about which contracting method to use. In PFI, in theory, any contracting method may be used, but in UK practice, the construction work in a PFI project is generally let under a DB contract.

GC unites management with design by virtue of the position of the architect (or civil engineer) in the process. As design leader and contract administrator, the architect is in control of most of the major decisions in a project. Moreover, general contracts usually contain mechanisms for the contract administrator to retain the final word on what constitutes satisfactory work. In building contracts, such items have to be described as such in the bills of quantities (for example JCT SBC 11, clause 2.3.3) whereas civil engineering contracts tend to reserve much wider powers of approval for the engineer (for example ICC 11, clause 13). GC therefore displays the least separation of design from management. (See Section 11.1)

On the face of it, DB contracts should also exhibit no separation of design from management since both functions lie within the same organization. While this is indeed true, it also means that where design issues must be weighed against simple cost or time exigencies, issues are resolved within the DB firm. This excludes the involvement of the client from such debates. Further, DB contractors are typically contractors first and designers second (though not always). The fact that DB projects are let on a lump sum will motivate the DB contractor to focus on time and cost parameters over other considerations.

110 Construction contracts

Least |

Most |

PBC

PFI

GC

DB

CM

Figure 7.5: Capacity for variations

In CM there is a clear and deliberate separation of design from management. The design leader has a role in co-ordinating and integrating design work, but the construction manager must ensure that design information is available at the right time and that trade contractors’ design is properly integrated. Additionally, the construction manager is typically the leader of the construction site.

7.5.3Reserving the client’s right to alter the specification

There are three reasons for altering the specification. First, the client may wish to change what is being built. Second, the design team may need to revise or refine the design because of previously incomplete information. And third, changes may be needed as a response to external factors. Although it is quite clear that a construction contract imposes obligations on the contractor to execute the work, it is often overlooked that this also gives the contractor a right to do the work and that right cannot lightly be taken away. If a client wishes to make changes to the specification as the work proceeds, or wishes to allow the design to be refined for whatever reason, then clauses will be needed to ensure this. The procurement decision affects the extent to which the contract structure (rather than clause content) facilitates changes, as shown in Figure 7.5.

General contracts typically contain detailed clauses defining what would be permitted as a variation, but common law restricts the real scope of variations clauses to those that could have been within the contemplation of the parties at the time the contract was formed.1 Therefore, despite extensive provisions for instructing and valuing variations, their true scope is limited. PBC would not normally involve the client in the design and construction process, rendering the opportunities to vary the specification as practically zero. PFI tends to involve the client along the lines of a DB contract, but with the role of the concessionaire intervening in the contract structure, there may be only a slight possibility to influence and change the specification. DB contracts usually lack the detailed contractual machinery and bills of quantities for valuing variations. Further, as a lump sum contract for an integrated package, variations to the specification are awkward and best avoided. CM involves a series of separate packages, each of which can be finally specified quite late in relation to the project’s overall start

1Blue Circle Industries plc v Holland Dredging Co (UK) Ltd (1987) 37 BLR 40, CA.

Risk allocation and procurement decisions 111

Least |

Most |

PBC

PFI

GC

DB

CM

Figure 7.6: Clarity of client’s contractual remedies

date, but before the individual package is put out to tender. Therefore, this procurement method has the highest flexibility.

7.5.4Clarity of client’s contractual remedies for defects

An important part of the contract structure is the degree to which the client can pursue remedies in the event of dissatisfaction with the process. Some contract structures are simple, enabling clear allocation of blame for default, whereas others are intrinsically more complex, regardless of the text of actual clauses. One of the fundamental aims behind a contract is to enable people to sue each other in the event of non-performance or mis-performance (defects). The relative ease with which contractual remedies can be traced is shown in Figure 7.6.

PBC involves a direct relationship between a buyer and a supplier based upon how a product will perform. Even when the product is a building, or item of infrastructure, the clarity of remedies relies almost exclusively on the clarity of the performance criteria. For example, as PBC for a highway based on traffic flow requires only the measurement of traffic flow to determine whether there has been a failure in the supply, this is a very clear route to a contractual remedy. PFI, by contrast, involves a complex network of contracts. While there is usually a performance-based contract at between the client and the concessionaire, the network of contracts and the potential for the involvement of the client on both the demand side and the supply side render this potentially a difficult situation.

The least clear contractual remedies arise from GC because the contractor is employed to build what the client’s design team has documented. Therefore, any potential dispute about some aspect of the work first has to be resolved into a design or workmanship issue before it can be pursued. The involvement of nominated sub-contractors typically makes the issue much more complicated and difficult. By contrast, DB with its single point responsibility carries clearer contractual remedies for the client because the DB contractor will be responsible for all of the work on the project, regardless of the nature of the fault. However, this clarity would be compromised if the client had a large amount of preparatory design work done before the contractor was appointed. Under CM, the direct contracts between client and trade contractor also help with clear lines of responsibility, but the involvement of a design team and a variety of separate trades, some with design responsibility, make the situation more complex than DB,

112 Construction contracts

Least |

Most |

PBC

PFI

GC

DB

CM

Figure 7.7: Complexity of projects

although not as complex as GC. PBC and PFI both have very clear lines of accountability, since the end user/tenant has a single relationship with the service provider. On the other hand, since the concessionaire or the landlord is the client for the purposes of the construction works, contractual recourse for faults depends entirely on the contracting method, so there is no line shown in Figure 7.6 in relation to this aspect. The answer to the question about contractual remedies is never PFI or PBC, since these are not contracting methods.

7.5.5Complexity of the project

Complexity cannot be considered in isolation because it is inextricably bound up with speed and with the experience of those involved with the project. It is also a very difficult variable to measure. Although technological complexity is a significant variable, it can be mitigated by using highly skilled people. Of more concern in the procurement decision is organizational complexity. Roughly speaking, this can be translated into the number of different organizations needed for the project. Because of fragmentation, this means that a project with a large number of diverse skills is more organizationally complex than a project with fewer skills, even though the few may be more technologically sophisticated. Each of the procurement methods can be used for a wide range of complexities, as shown in Figure 7.7, but the limits differ.

PBC is a method of buying things that applies in practice to anything. From a piece of cutlery to the complete development of a major infrastructure project, the deal can be set up on a value-based price with the vendor funding the entire development. Thus, PBC may be applied from the simplest to the most complex project. PFI, on the other hand, requires a large up-front effort in setting up the finance and going through a complex and difficult tendering process. This overhead makes it inappropriate for simple projects.

GC involves an organizational structure that is probably too complex for simple projects. The idea of fully designing or specifying all of the work to be done before a contractor bids for it assumes that the design is beyond the skill of the contractor. In simple projects this is not so and it would be better to rely on the skill and judgement of a contractor by utilizing DB. Complex projects may require nominated sub-contracts because of the need to incorporate the design skills of specialist trade contractors. When this forms a large part of the contract work, GC

Risk allocation and procurement decisions 113

Least |

Most |

PBC

PFI

GC

DB

CM

Figure 7.8: Speed from inception to completion

breaks down as it is based on the assumption that the main contractor will be doing most of the work, not simply managing work of others. With its single point responsibility, DB is ideal for simple jobs but this does not preclude its use for more sophisticated work. However, if the project is too complex, DB contractors may lack the experience and skill needed for the high levels of co-ordination and integration required. For very complex projects, CM is suitable. Perhaps construction managers tend to be more experienced, but the contract structure of CM means that the construction manager should have no vested interest in conflicts between design and fabrication exigencies or between trade contractors. This independence, coupled with a professional management role, renders CM ideal for dealing with organizational complexity. However, there is no reason to avoid CM just because a project is simple. It has been used with great success on small projects where the participants are familiar with CM and with each other.

7.5.6Speed from inception to completion

One of the most distinctive features of construction projects is the overall duration of the process. Since a single construction project typically constitutes a large proportion of a client’s annual expenditure and a large proportion of a contractor’s annual turnover, each project is individually very important. Many developments and refinements to procurement methods have been connected with a desire to reduce the duration of projects. Much of the process of construction is essentially linear. Briefing, designing, specifying and constructing must follow one from the other. If these steps can be overlapped, then the overall time can be reduced significantly, provided that there is no need for re-work due to changes and wrong assumptions, in which case too much overlapping can slow the process and cancel any gains due to overlapping.

Figure 7.8 shows a wide range of possibilities for PBC. It may offer an extremely quick solution in the building sector, since speculative developers may have completed buildings ready for occupation. There is little to do other than finding the building and negotiating the lease. In infrastructure projects, there will not be completed projects awaiting negotiation, but a PBC may still be used for aspects of a project that may be out-sourced to suppliers with standard items of plant or equipment ready to deliver. But PBC may involve a complex, drawn-out process for identifying funding, time for design and development and so on, leading to a potentially long process. Because of the need to procure finance and

|

114 Construction contracts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Least |

|

|

|

Most |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PBC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PFI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

GC |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

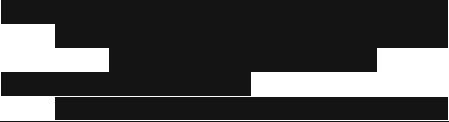

Figure 7.9: Certainty of price

take tendering consortia through a bidding process that includes design work, PFI tends not to be a quick solution. Similarly, the need in GC to design and specify the whole of the works before inviting tenders, means that GC is generally one of the slower methods. This overall slowness often leads to techniques for starting on site early such as the letting of early enabling contracts, like demolition or earthworks. Another technique to speed progress is to leave much of the detailed design until after the contract has been let by including large provisional sums in the bills of quantities, a bad practice that should generally be avoided. Other procurement methods are inherently quicker simply because they enable an early site start. Since a DB contractor will be undertaking design, early assumptions are fairly safe. Further, DB is generally used for projects that are straightforward. CM can be very quick because the relationships are conducive to quick working and overlapping.

7.5.7Certainty of price

Price certainty is not the same as economy. It is doubtful that there is any correlation between economy and procurement method. The reliability of initial budgets is highly significant for most clients. However, this must be weighed against the financial benefits of accepting some of the risks and with them, less certainty of price.

Figure 7.9 shows that PBC and PFI are at opposite extremes in terms of certainty of price. PBC offers certainty because, in principle, it is a contract for performance and the buyer only pays the agreed amount when the service is being delivered. PFI involves setting up contracts and agreements long before there is any certainty of the required performance or the design. Therefore, it is some way into the process before there is certainty of price for the buyer.

GC comes in a wide variety of forms. One of the most wide ranging variables is the pricing document, the bill of quantities. This may be a fully measured bill (known as ‘with quantities‘), a bill of approximate rates (‘approximate quantities’) or there may be no quantities at all (‘without quantities’). However, even with a schedule of rates, contractors are paid according to their own pre-priced estimates in line with the principles of fixed price contracts explained in Section 7.3. Therefore, Figure 7.9 shows that GC tends toward the more certain but there is a huge range of variability in this because the final price depends on many other factors such as the adequacy of the initial budget, the quality of the design and so on. By contrast, DB is a contract for a lump sum for all of the work required.

Risk allocation and procurement decisions 115

Although the contractor may add contingencies in to the price to deal with the unexpected, they remain the responsibility of the contractor. This may, in theory at least, result in a higher price, but the benefit is that the final price is agreed at the outset. Finally, CM consists of a series of contracts, which are let as the work proceeds. Therefore, it is impossible to be confident about the final price until the project is nearly completed. Moreover, there is no fundamental reason to prevent some of the contracts being let as cost reimbursement packages.

7.5.8Balancing the requirements

The seven individual criteria provide an indication of how no single procurement solution can satisfy all requirements. A selection process can never be comprehensive: it is merely a technique for recording observations and views. The aim of the Figures is to act as a vehicle for guiding the client through the decision. Clearly, there may be other, more important factors for particular clients. Similarly, some of the factors chosen here may not apply to every project. However, the principle remains. Before entering into contracts, a client should be advised about the major areas of risk and the suitability of various procurement options so that an appropriate procurement method can be identified.

This page intentionally left blank