Учебник по НТП

.pdf

How to make a concept map:

1. Start with a list of concepts or ideas to be mapped. This list should be complete enough to allow you to choose the main idea of the map.

2.Write the main idea in the center of the page, and draw a circle around it. For the major subject subheadings, draw lines out from this circle.

3.Look through the list to identify the concept words that directly relate to the main idea and place them in order of priority below or around the main idea.

4.Use lines to connect the concepts based on relationships that link them and label these lines with the subheadings. You may want to color shapes, arrows or words for emphasis.

5.If you come to a standstill, look over what you have done to see if you have left anything out.

6.Make sure the concepts are succinctly represented in no longer than 3 words. The arrangement of concepts should be hierarchical from general to specific.

Remember: There are no perfectly correct concept maps, only maps that come closer to the meanings you have for those concepts. As the mapmaker, you must make it correct for you.

Make up a concept map on Physical Science and fill

Science and fill it with basic ideas, associated words and phrases you’ve learned in this unit.

it with basic ideas, associated words and phrases you’ve learned in this unit.

23

Unit II

Chemical Science

I. Getting Started

Read the text “The Periodic Table“. Divide it into several key parts and compose 3-5 questions to the each part. Put your questions to class.

key parts and compose 3-5 questions to the each part. Put your questions to class.

II. Working With Vocabulary

Place the words and phrases below into the “Word“ column and com- plete the table:

Word |

English |

Examples |

Russian |

|

definition |

of usage |

translation |

||

|

tabular display, melting point, atomic volume, chemical family, stoichiometry, atomic number, chemical symbol, alkali metal, reactive metal, outer shell, ionic bonding, alkaline earth element, oxidation number, transition metal, valence electron, colored compound, catalyst, metalloid, semi-conductor, non-metal, metallic luster, halogen, noble gas, inert gas, rare earth element.

III. Practising Translation Techniques

Make a written translation of the following text:

The Periodic Table

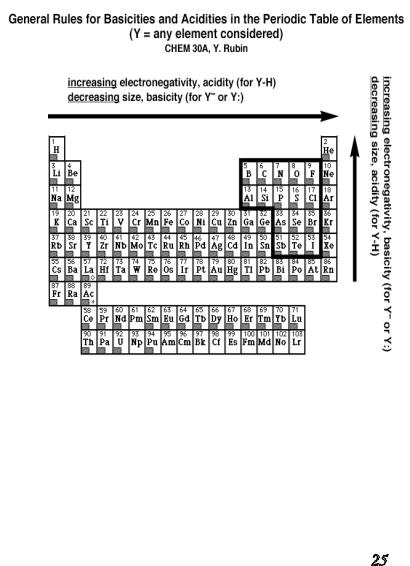

The periodic table of the chemical elements is a tabular display of the known chemical elements. Chemists Dmitrii I. Mendeleev, a Russian, and German Lothar Meyer were working independently in 1868 and 1869 on the arrangement of elements into seven columns, corresponding to various chemical and physical properties. Their tables were simi- lar—they acknowledged each other’s work—the differences are subtle but important: Meyer’s table was an accurate (for the time) accounting of the known facts about each element, such as melting point and atomic volume. His table clearly showed the existence of periodic chemical

families.

Mendeleev presented a much bolder and scientifically useful table. His paper, On the Relation of the Properties to the Atomic Weights of the

24

Elements, was enthusiastically received by the Russian Chemical Society. In it, the periodic relationship between chemical groups, that is, elements with a similar stoichiometry of reaction, is clearly illustrated. Each element is listed by its atomic number and chemical symbol. There are 116 chemical elements whose discovery has been confirmed; 94 can be found naturally on Earth, and the rest have been produced in laboratories.

The element groups or families include:

The alkali metals, found in group 1 of the periodic table, are very reactive metals that do not occur freely in nature. These metals have only one electron in their outer shell. Therefore, they are ready to lose that one electron in ionic bonding with other elements. As with all metals, the alkali metals are malleable, ductile, and are good conductors of heat and electricity. The alkali metals are softer than most other metals. Cesium and Francium are the most reactive elements in this group. Alkali metals can explode if they are exposed to water.

The alkaline earth elements are metallic elements found in the second group of the periodic table. All alkaline earth elements have an oxi-

25

ter, and do not reflect light. They have oxidation numbers of ±4, -3, and -2. The non-metal elements include the most common elements for an everyday use, such as Hydrogen, Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen, Phosphorus, Sulfur, Selenium.

The halogens are five non-metallic elements found in group 17 of the periodic table. The term “halogen” means “salt-former” and compounds containing halogens are called “salts”. All halogens have 7 electrons in their outer shells, giving them an oxidation number of -1. The halogens exist, at room temperature, in all three states of matter: Solid—Iodine, Astatine; Liquid—Bromine; Gas— Fluorine, Chlorine.

The six noble gases are found in group 18 of the periodic table. These elements were considered to be inert gases until the 1960’s, because their oxidation number of 0 prevents the noble gases from forming compounds readily. All noble gases have the maximum number of electrons possible in their outer shell making them stable (2 for Helium, 8 for Neon, Argon, Xenon, etc.).

The thirty rare earth elements are composed of the lanthanide (Samarium, Cerium, Lutetium, etc.) and actinide (Thorium, Plutonium, Mendelevium, etc.) series. One element of the lanthanide series and most of the elements in the actinide series are called trans-uranium, which means synthetic or man-made. All of the rare earth metals are found in group 3 of the periodic table, and the 6th and 7th periods.

IV. Knowing Ins And Outs

The names of many chemical elements were coined from Greek, Latin and German roots, names of persons (eponyms) and geographical locations (toponyms). For example, Rhodium (Rh) got its name for the rose color of its salts, Rhodon in Greek means rose. The Swedish chemist Per Theodor Cleve derived the name Holmium (Ho) for his native city, and Thulium (Tm) from Thule, an old name for Scandinavia.

Study the list of chemical elements below, trace their etymological

elements below, trace their etymological mod- els and translate the names of the elements into Russian. Provide exam- ples of English and Russian words with the same roots (if possible).

mod- els and translate the names of the elements into Russian. Provide exam- ples of English and Russian words with the same roots (if possible).

Silicon, Germanium, Curium, Promethium, Francium, Magnesium, Phosphorus, Bohrium, Vanadium, Iridium, Calcium, Hydrogen, Lithium, Mendelevium, Titanium, Chromium, Ruthenium, Samarium, Nobelium, Osmium, Selenium, Chlorine, Xenon, Krypton, Neon, Helium, Thorium, Lutetium, Rubidium, Gallium, Iodine, Cobalt, Wolfram (Tungsten), Zinc, Oxygen, lanthanum, Unununium.

27

V. Enhancing Skills In English-Russian Interpretation

Render orally the following text:

The Composition Of Fireworks

Although the art of fireworks dates back to ancient China, most of the typical effects are inventions of our century. A classical example is the development of coloured flames. Before the 19th century, only various yellows and oranges could be produced with steel and charcoal. Chlorates, an invention of the late 18th century and an industrial product of the 19th century, added basic reds and greens to the pyrotechnist’s repertoire. Good blues and purples were not developed until this cen-

tury.

The light emitters can be grouped into two main categories: solid state emitters (black body radiation) and gas phase emitters (molecules and atoms). A black body is an ideal emitter which is capable of absorbing and emitting all frequencies of radiation uniformly. The exitance M of the black body, the power emitted per unit area, is defined as:

M = sT4,

where s is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. Thus, we could obtain a twofold increase in radiation by merely increasing the flame temperature from, say 2000 K to 2400 K. Furthermore, the radiation also shifts from infrared to visible light as the temperature increases. The calculated emission spectrum (the energy per unit volume per unit wavelength range) has the following shape:

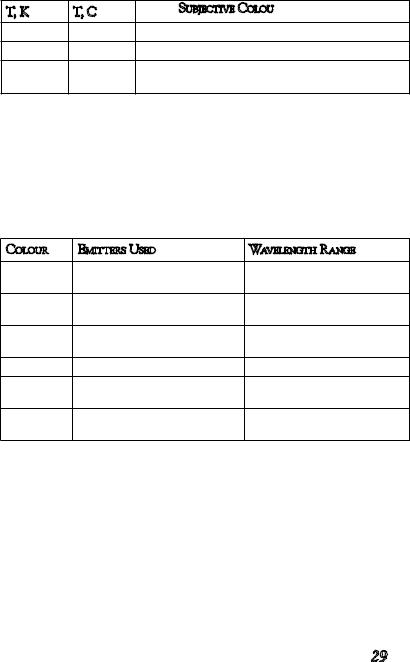

In the real world, simplified models are not of much help. Many solids do emit light in the same relative proportions as a black body, but not in the same amounts. The emissivity of a solid substance is the factor relating radiant energy. The emissivities of many refractory metals and metal oxides are higher in the short wavelength end of the visible spectrum—that is, they look bluer than expected when heated. Table 1 gives a summary of visual temperature phenomena of solid bodies - for instance, a glowing piece of charcoal, a good approximation to the black body.

T, K |

T, C |

Subjective Colour |

750 |

480 |

faint red glow |

850 |

580 |

dark red |

1000 |

730 |

bright red, slightly orange |

1200 |

930 |

bright orange |

28

T, K |

T, C |

Subjective Colour |

1400 |

1100 |

pale yellowish orange |

1600 |

1300 |

yellowish white |

>1700 |

>1400 |

white (yellowish if seen from a dis- |

|

|

tance) |

As we can see from the table above, it is not possible to produce anything but shades of orange and yellow with grey-body emitters. For other colours, we need specific emitters of coloured light. Surprisingly few emitters are used in pyrotechnics, given the vast range of atomic and especially molecular spectra available. There are not many, because there are no commercially useful emitters available in the 490-520 nm region (blue-green to emerald green). The table below summarises the sources of coloured light used in today’s fireworks.

Colour |

Emitters Used |

Wavelength Range |

Yellow |

Sodium D-line atomic emis- |

589 nm |

|

sion |

|

Orange |

CaCl, molecular bands |

591599 nm, 603-608 nm |

|

|

being the most intense |

Red |

SrCl, molecular bands |

617-623 nm, 627-635 nm, |

|

|

640-646 nm |

Red |

SrOH, molecular bands |

600-613 nm |

Green |

BaCl, molecular bands |

511-515 nm, 524-528 nm, |

|

|

530-533 nm |

Blue |

CuCl, molecular bands |

403-456 nm, less intense |

|

|

bands 460-530 nm |

However, the emitting molecules, especially SrCl and BaCl, are so reactive that they cannot be packed directly into a firework. To generate them, we need pyrotechnic compositions designed to generate the above molecules, to evaporate them into the flame and to keep them at as high temperature as possible to achieve maximum light output. The colours of aerial fireworks come invariably from stars— small pellets of firework composition which contain all the necessary ingredients for generating coloured light or other special effects. They may be as tiny as peas or as large as strawberries.

To generate the emitting molecules at a sufficiently high temperature, a fuel-oxidiser system (pine root pitch - potassium perchlorate) is used. Strontium carbonate is used as the Sr source, and chlorine comes from potassium perchlorate. An excess of fuel is used to pre-

29

vent the formation of SrO, which would solidify in the flame and emit grey body radiation. This will result in a “washed-out” colour.

A typical red star might contain:

Potassium perchlorate |

67% by weight |

|

|

Strontium carbonate |

13.5% |

|

|

Pine root pitch (fuel) |

13.5% |

|

|

Rice starch (binder) |

6% |

|

|

Organic fuels, such as pine root pitch, various gums and rosins and synthetic resins, cannot generate as high temperatures as metallic fuels. The pyrotechnist is tempted to use powdered magnesium and aluminium for his/her brilliant stars, because they provide an easy method of raising the flame temperature and increasing the brightness.

Unfortunately, the molecular emitters are quickly destroyed if the flame is too hot. CuCl is probably the most fragile colour emitter. It can be used with metallic fuels only with difficulty. Consequently, blue stars are never very bright. Another problem with metals are their oxidation products, metal oxides, which are powerful grey body radiators due to their refractory nature. Their incandescent glow can easily wash out all colours.

VI. Enhancing Skills In Russian-English Interpretation

Render orally the following text:

Искусство небесного огня

огня

Bсовременных снарядах для фейерверков используется старейший пиротехнический состав—черный порох, одновременно выполняющий функции метательного и взрывчатого вещества.

Черный (или дымный) порох был изобретен в Китае более 1000 лет назад с целью использования его в простейших ракетах и шутихах. В средние века сведения о черном порохе постепенно распространились на Запад. В 1242 г. английский монах Роджер Бэкон раскрыл свою формулу взрывчатой смеси в качестве зашиты от обвинений в колдовстве. Он считал эту смесь настолько опасной, что зашифровал ее состав. В XIV в. были созданы такие виды оружия, как мушкеты и пушки, в которых в качестве метательного вещества применялся черный порох.

Формула черного пороха по существу не претерпела изменений на протяжении веков: это известная смесь нитрата калия (широко

30

известной калиевой селитры), древесного угля и серы в отношении 75:15:10 по весу. По-видимому, черный порох остается практически единственным химическим изделием, в котором сегодня применяются такие же компоненты, в такой же пропорции и который изготавливается по такой же технологии, как и во времена Колумба. Это завидное постоянство отражает тот факт, что порох является почти идеальным пиротехническим составом, настолько стабильным, что его можно хранить десятилетиями, не опасаясь разложения, если содержать сухим.

Teacher: What is the formula for water? Student: H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O

Teacher: That’s not what I taught you.

Student: But you said the formula for water was...H to O!

Пиротехнический процесс в принципе не отличается от обычного горения. В состав пиротехнической смеси входят источник кислорода (окислитель) и горючее вещество (восстановитель). Они представляют собой обычно отдельные твердые химические реагенты, которые должны быть механически смешаны. При нагревании происходит реакция с обменом электронами, или, иначе, окис- лительно-восстановительная реакция.

Наиболее известным пиротехническим эффектом фейерверка являются “брызги” света. Их цвет зависит от длины волны излучения. Видимый свет представляет собой электромагнитное излучение в диапазоне длин волн от 380 до 780 нм (1 нм = 10-9 м). Свет

снаибольшей длиной волны воспринимается глазом как красный,

асвет с наименьшей длиной волны—как фиолетовый. Светящийся объект виден как белый, если излучает во всем видимом спектре. Если большая часть световой энергии излучается в пределах узкой полосы длин волн, то цвет такого излучения будет соответствующим данному участку спектра.

Пиротехнические составы излучают свет при трех основных процессах: температурном свечении (тепловое излучение абсолютно черного тела), атомарном излучении и молекулярном излучении. Температурное свечение имеет место в случае с нагреванием в пламени твердых тел или жидких частиц до высоких температур. Горячие частицы излучают в широком спектре, освобождаясь при этом от избыточной энергии. Чем выше температура, тем короче длина волны излучаемого света. Интенсивность излучения пропорциональна четвертой степени температуры пламени, поэтому незначительное повышение температуры приводит к резкому усилению яркости.

31

Белые сигнальные ракеты содержат в своем составе в качестве горючего химически активный металл типа магния. Твердые частицы оксида, образующиеся при окислении металла, нагреваются до температуры более 3000°С, до “белого каления”. Смесь перхлората калия и мелкого алюминиевого или магниевого порошка обеспечивает получение яркой вспышки белого света. Такого рода составы для “фотовспышек” или “вспышек с грохотом” находят широкое применение—от изготовления шутих до создания специальных эффектов на концертах рок-музыки и мгновенного освещения при ночной фотографической съемке.

Более крупные частицы металла продолжают оставаться горячими дольше, чем частицы порошка, и способны гореть за счет кислорода воздуха. Такие частицы образуют искры белого света, мгновенных вспышек они не дают. Чем крупнее частица, тем дольше длится искра. Частицы железа и древесного угля не нагреваются так сильно, как частицы активных металлов; они могут быть нагреты только до 1500°С, вследствие чего образуют менее яркие золотистые искры.

Натрий является одним из наиболее мощных атомарных светоизлучателей. Нагретые до температуры выше 1800°С атомы натрия испускают желто-оранжевый свет длиной волны 589 нм. Этот процесс характеризуется такой эффективностью, что даже незначительное количество натрийсодержащих примесей способно свести на нет усилия по получению пламени любого другого цвета.

В иных случаях мощное натриевое свечение может оказаться полезным. Окислитель из нитрата натрия в смеси с магниевым горючим является основным составом, который применяется в армии США для освещения местности при проведении ночных операций. Высокие температуры (порядка 3600°С), характерные для магниевого пламени, расширяют диапазон длин волн, излучаемых атомами натрия. В результате обеспечивается освещение ярким белым светом.

Аналогично атомарному излучению молекулярное обусловлено переходом электронов из основного состояния в возбужденное. В пиротехническом пламени молекулы должны присутствовать в газообразной форме и должны быть нагреты до температуры, достаточно высокой для обеспечения перехода в возбужденное состояние с последующим излучением. Если пламя слишком горячее, молекула разлагается на составляющие ее атомы и не излучает света. Более того, чтобы получились яркие цвета, необходимо обеспечить достаточно высокую концентрацию молекул в пламени, однако требуется свести к минимуму образование жидких и твердых частиц, поскольку они являются источником температурного свечения, “размывающего” нужный цвет.

32