учебный год 2023 / (Encyclopedia of Law and Economics 5) Boudewijn Bouckaert-Property Law and Economics -Edward Elgar Publishing (2010)

.pdfAdverse possession 185

to rely on an error, for instance by improving the property or development (Miceli, 1997). Without a limitation period, a true owner would indefinitely be in a position to exercise his or her property rule protection in order to extract payments while the reliance costs of the adverse possessor increase over time with his or her investments in the property. Accordingly, by imposing a time-limited property rule, the doctrine of adverse possession provides owners incentives to correct errors in a timely manner and limits the ability to appropriate quasi-rent from adverse possessors that have relied in good faith on a boundary mistake (Miceli, 1997).

C.The requirements of adverse possession

For the rules of adverse possession to apply, a few interrelated conditions have to be met. The possessor must hold the property actually, exclusively, continuously, in open and notorious manner, and adversely to the owner, with a claim of right. The interpretation of these conditions has been the subject of debate and the interpretation differs between states (see Netter, Hersch and Manson, 1986). Generally, it is required that the possessor holds the possession exclusive from others for a period at least as long as the statutory period, without being dispossessed (continuously), in an open and visual manner that is inconsistent with the title of the owner (adverse) and without the owner’s permission (hostile). With the exception of variations in time periods and some minor differences the doctrine of adverse possession under common law does not differ much from that found in most civil law systems.

The above conditions comport quite naturally with the purposes of adverse possessions set out in the previous section. Especially the reward/ punishment explanation of adverse possession seems to justify the legal requirements of adverse possession. For instance, if adverse possession is to punish land owners that fail to act and alert good faith possessors before the latter rely on the use of land that they do not own, it is within reasonable expectations that such duty is imposed only if the acts of adverse possession are reasonably visible (open and notorious) and provide sufficient signal to the outside world that the adverse use is premised on an ownership claim (exclusive possession, claim of right). Similarly, the protection of any reliance interest on behalf of the adverse possessor is warranted only if the possessor has made sufficient use of the property (continuous) in a manner that would traditionally be associated with ownership (exclusive, with claim of right). Similarly, the legal conditions of adverse possession fit well the purpose of reducing the occurrence and costs of boundary mistakes. The requirements that possession during the statutory period must be actual, open, notorious and exclusive ensure to the true owner

186 Property law and economics

an opportunity to discover boundary errors prior to investment by the encroacher (Miceli and Sirmans, 1995b).

One notable difference between the rule of adverse possession within civil law and common law systems is the significance of the state of mind of the adverse possessor (‘does the adverse possessor realize that the property is not his/hers?’). In the United States there is a debate whether the intention of the possessor matters for the applicability of the adverse possession doctrine. The so-called Maine rule (mistaken possession is not found to be sufficiently hostile to the owner’s right) has generally been abandoned in favor of the newer Connecticut rule which emphasizes that the possessor’s state of mind is irrelevant. While this represents a formal legal shift from the favorable treatment of bad faith possessors – which is more in line with the punishment theory of adverse possession – to include also good faith possessors as potential benefactors of adverse possession – corresponding with the reward and incentive theories – judicial practice has traditionally favored good faith possessors, often by manipulating the application of the conditions to the facts so that good faith possessors may acquire ownership through adverse possession (Helmholz, 1983). By contrast, most civil law systems more explicitly distinguish between good and bad faith adverse possessors. Generally, prescription periods are longer for bad faith possessors than for good faith possessors.

Distinctions between good and bad faith possessors are difficult to justify from the perspective of the evidence costs-reducing justification of adverse possession. Good faith errors are difficult, often impossible, to distinguish from intentional errors, for instance with regard to real property issues such as boundary encroachments (Bouckaert and De Geest, 1998). Any attempt to prove bad faith might significantly increase high litigation costs, notably if the plaintiff must reverse the presumption of good faith against the defendant possessor. Also, the current, differing treatment of good and bad faith possession does not sit comfortably with the reward and punishment explanations of adverse possession. If the focus of adverse possession is on preventing good faith mistakes and preventing strategic behavior on behalf of the true owner, adverse possession can simply be limited to good faith possession. By contrast, the adverse possession suggest to reward productive use of property that is held by dormant land owners, especially bad faith possessors should be awarded for making productive use of resources, provided that sufficient notice is provided to landowners (see for example Fennell, 2006, suggesting bad faith oriented system of adverse possession).

On the other hand, there are economic arguments in favor of extending the prescription period of bad faith possessors. Prolonging the prescription period likely reduces the incidence of preying by squatters and the

Adverse possession 187

consequences demoralization costs on behalf of surprised landowners that are faced with a completed adverse possession period (Ellickson, 1986). In this vein, Thomas Merrill has argued in favor of adjusting the rule of adverse possession to provide liability rule protection against bad faith possession (Merill, 1985). Such remedial shift, from property rule to liability rule protection, on behalf of a true owner at the end of the prescription period of a bad faith possession, reduces the incentives of a true owner to be vigilant, but likely reduces the lure of preying on behalf of bad faith adverse possessors (in this manner it has a similar effect as a lengthening of the prescription period, see below).

D.The Optimal Prescription Period

Adverse possession essentially involves the following efficiency trade-off between the adverse possessor and the true owner: a shorter statutory period reduces uncertainty as to the title in subsequent transfers, while a longer statutory period reduces the costs to property owners to protect their land from potential adverse possessors.

On the other hand, there are costs to the application of the adverse possession doctrine. With the risk of losing title, owners must monitor their land. When they are not using the property they need to be careful not to lose ownership to a possessor. By reducing the costs of mistakes of encroachments, adverse possession introduces a moral hazard problem, in the sense that there is less incentive to make sure mistakes are not made in the first place (Netter, 1998).

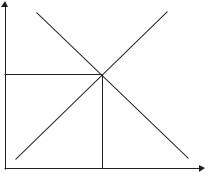

Figure 8.1 illustrates this trade-off. At point e, where the time of occupation (on the vertical X-axis) required to obtain title is set optimally, a balance is found between prevention and uncertainty costs. As the

Toccupation

topt

PC/MC |

UC |

|

e |

Limitation period

Figure 8.1 Optimal prescription period

188 Property law and economics

limitation period is set beyond point e, the uncertainty costs, represented by the UC curve, increase further. The longer the statutory period is set, the lower the monitoring costs of owners. If the limitation period is set below e, the prevention and monitoring costs, as represented by the PC/ MC curve. increase while uncertainty costs reduce.

Economic theory holds that the greater the benefit from reducing uncertainty with regard to the ownership of a good, the shorter should be the time period required of adverse possession.

A fairly recent study of prescription statutes in the different North American states (Netter, Hersch and Manson, 1986) provides empirical evidence on the various differences and examines the determinants of the length of the occupation period in the statutes of limitations of states’ adverse possession at the time of statehood.

First, a negative relationship between property value in a state and statute length was observed. When the property has great value, there is simply a higher return to be obtained from ending potential disputes about ownership that arise from mistakes. Also, the costs of mistakes are higher when property value is high. In such circumstances it is recommendable that adverse possession requirements (length, type of possession) are less demanding. However, it should be acknowledged that if property values are high, owners have more to lose from adverse possession.

Secondly, a positive relationship between population density and statute length was found. As population density increases more property transfers take place, which raises the probability that errors (in determination of boundaries, identification of the title holder, registration, and so on) will occur. The length of the prescription period will affect incentives in various ways.

Protection costs will be lower when protection periods are relatively long. The shorter the prescription time period, the more theft or deceit is encouraged. Stolen, lost and fraudulently acquired goods will have a higher market price when potential buyers know that the possibility of claims and other repossession actions are restricted to only a limited period of time. Thus, the introduction of a prescription period will affect criminality and tortuous acquisition rates. The possibility of becoming a true owner through mere adverse possession increases the value of an adversely possessed good. A thief who wants to resell the stolen good will be able to charge a higher price to the buyer under a system where the latter can become the legally unchallenged owner after the elapse of a short period of time. As theft, fraudulent and deceptive acquisition will become more profitable, property owners will need to invest more into protection of the property.

Also, short prescription periods force owners of lost, stolen or

Adverse possession 189

fraudulently divested goods to concentrate their search and repossession acts within a short period of time, which leads to higher opportunity costs of search (Bouckaert and De Geest, 1998). On the other hand, short prescription periods provide the possessor with efficient incentives with regard to investment decisions.

Bibliography

Anderson, Terry L. and Lueck, Dean (1992), ‘Land Tenure and Agricultural Productivity on Indian Reservations’, 35 Journal of Law and Economics, 427–454.

Baird, Douglas G. (1983), ‘Notice Filing and the Problem of Ostensible Ownership’, 12

Journal of Legal Studies, 53–67.

Baird, Douglas G. and Jackson, Thomas H. (1984), ‘Information, Uncertainty, and the Transfer of Property’, 13 Journal of Legal Studies, 299–320.

Bouckaert, B. and De Geest, G. (1998), ‘The Economic Functions of Possession and Limitation Statutes’, in Ott, C. and von Wagenheim, G., Essays in Law and Economics IV, Antwerpen and Apeldoorn, Maklu, 151–168.

Bowles, Roger A. and Phillips, Jennifer (1977), ‘Solicitors’ Remuneration: A Critique of Recent Developments in Conveyancing’, 40 Modern Law Review, 639–650.

Callahan, C. (1961), Adverse Possession, Columbus, Ohio State University Press.

Cooter, Robert D. (1991), ‘Inventing Market Property: The Land Courts of Papua New Guinea’, 25 Law and Society Review, 759–801.

Cooter, Robert D. (1992), ‘Organization as Property: Economic Analysis of Property Law and Privatization’, in Clague, Christopher and Rausser, Gordon (eds), The Emergence of Market Economies in Eastern Europe, Oxford, Blackwell, 77–97.

Crawford, Robert G., Klein, Benjamin and Alchian, Armand A. (1978), ‘Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process’, 21 Journal of Law and Economics, 297–326.

Ellickson, R. (1986), ‘Adverse Possession and Perpetuities Law: Two Dents in the Libertarian Model of Property Rights’, 64 Washington University Law Quarterly, 723–737.

Epstein, Richard A. (1979), ‘Possession as the Root of Title’, 13 Georgia Law Review, 1221 ff. Fennell, Lee Anne (2006), ‘Efficient Trespass: The Case for “Bad Faith” Adverse Possession’,

1037, Northwestern University Law Review, 1073–1075.

Frech, H. Edward III (1991), ‘Review of Contracting for Property Rights, by Gary D. Libecap’, 15 Journal of Comparative Economics, 536–538.

Goldberg, Michael A. and Horwood, Peter J. (1987), ‘The Costs of Buying and Selling Houses: Some Canadian Evidence’, 10 Research in Law and Economics, 143–159.

Helmholz, Richard H. (1983), ‘Adverse Possession and Subjective Intent’, 61 Washington University Law Quarterly, 331–358.

Janczyk, Joseph T. (1977), ‘An Economic Analysis of the Land Title Systems for Transferring Real Property’, 6 Journal of Legal Studies, 213–233.

Janczyk, Joseph T. (1979), ‘Land Title Systems, Scale of Operations, and Operating and Conversion Costs’, 8 Journal of Legal Studies, 569–583.

Kennedy, Duncan (1981), ‘Cost-Benefit of Entitlement Problems: A Critique’, 33 Stanford Law Review, 387–445.

Lueck, Dean and Anderson, Terry L. (1992), ‘Agricultural Development and Land Tenure on Indian Country’, in Anderson, Terry L. (ed.), Property Rights and Indian Economics, Lanham, MD, Rowman and Littlefield Press.

Mascolo, E. (1992), ‘A Primer on Adverse Possession’, 21 Connecticut Bar Journal, 297–326.

Merrill, T. (1985), ‘Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Adverse Possession’, 79 Northwestern University Law Review, 1122–1154.

Miceli, Thomas J. (1997), Economics of the Law, New York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997.

190 Property law and economics

Miceli, Thomas J. and Sirmans, C.F. (1995a), ‘The Economics of Land Transfer and Title Insurance’, 10 Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 81–88.

Miceli, Thomas J. and Sirmans, C.F. (1995b), ‘An Economic Theory of Adverse Possession’,

15 International Review of Law and Economics, 162–173.

Miceli, Thomas J. and Turnbull, G.K. (1997), ‘Land Title System and Incentives for Development’, 14th Annual Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics, University of Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain.

Miceli, Thomas J., Sirmans, C.F. and Turnbull, G.K. (1998), ‘Title Assurance and Incentives for Efficient Land Use’, 6(3) European Journal of Law and Economics, 305–322.

Netter, J.M. (1998), ‘Adverse Possession’, in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, London, Macmillan.

Netter, J.M., Hersch, P.H. and Manson, W.D. (1986), ‘An Economic Analysis of Adverse Possession Statutes’, 6 International Review of Law and Economics, 217–227.

Schechter, Dan S. (1988), ‘Judicial Lien Creditors Versus Prior Unrecorded Transferees of Real Property: Rethinking the Goals of the Recording System and Their Consequences’,

62 Southern California Law Review, 105–186.

Williams, Philip L. (1993), ‘Mabo and Inalienable Rights to Property’, 103 Australian Economic Review, 35–38.

9Title systems and recordation of interests

Boudewijn Bouckaert

1.Title systems. Definition, history and types

A title system is a legal institution by which written evidence on the legal status of assets is systematically recorded. The written evidence mostly concerns acts of conveyances, providing data on the transfer of the asset, or on the vesting of partial rights, various interests or security rights on the asset. Their most prominent aim is to facilitate market circulation of assets by providing to potential buyers certainty about the legal status of the traded good. Often title systems serve also fiscal aims as they provide tax collectors with information on the wealth of taxpayers. The legal consequences of recordation can vary. Sometimes recordation is limited to the passive collection of conveyances and merely consists of a systematisation of already existing written evidence. Sometimes recordation has a deeper legal impact as the recordation implies also a procedure of checking the validity of written evidence and the rights and interests mentioned in it. In this case invalid rights and interests are purged from the asset (see further 4. Registration or recording system). In modern nation states title systems are most often organized by the government. They are a vital part of civil administration. As shown further, this was not always the case. Also nowadays recordation of rights and interests is often provided through private initiative. Major examples here are the registers of the title insurance companies in the USA and the Art Loss Register set up by major business from both the insurance and art industries.

As soon as trade expanded across the boundaries of small and informal groups, institutions, generating public knowledge on the legal status of the transferred assets emerged. The Athenians, for instance, posted a slab known as horos on land in order to signal that the land was under the charge of a security interest (Arrunadã, 2003, 6). In Roman law the transfer of land was sometimes operated through a court procedure in which the purchaser stated that the land was his. Because there was no opposition he was awarded ownership (in iure cessio). The simulated trial provided public knowledge on the transfer (Kaser, 1971). Also the other legal form of transfer, the mancipatio, involved ceremonies providing some publicity to the transfer (Garro, 2004, 13; Kaser, 1971). In Hellenistic Egypt recordation was particularly well developed. In each district a book, entering all transactions affecting land and slaves (diastromata) was kept. Certificates

191

192 Property law and economics

on the legal status of land (katagraphé) were enacted by a public officer (agronomos) (Garro, 2004, 14). In feudal Europe land tenures were mostly transferred by a ceremony held in a public place such as a market, church or court (Garro, 2004, 18). After the Middle Ages attempts were made by the central state to organize title systems covering the whole country. The customary law of the most northern part of France (pays de nantissement) provided already a system of recordation of titles. By an Edict of Colbert this recordation system was introduced in the whole country. Fierce opposition by the nobility and the notaries forced Colbert to repeal the Edict in 1674. The former did not like disclosing the highly encumbered status of their land. The latter feared the loss of absolute control exercised in dealings with immovable property (Garro, 2004, 19). After the French Revolution title systems were introduced for the recordation of mortgages (Code Hypothécaire of 1795). These were, however, again abolished by the enactment of the Code Civil. The drafters of the Code, inspired by the natural law consensualistic doctrine on transfers, considered transfers as an exchange, merely affecting the legal position of the contracting parties and in which the wider public had no business at all. The negative impact of this was felt quite soon in the financing sector and credit financing supported by immovable property was grossly impaired (Garro, 2004, 22). To repair this deplorable situation the law on transcription of mortgages, providing also for the recordation of all transfers of land and the vesting of all property rights and interests (rights in rem) on land, was enacted in 1855.

Also in Germany recordation of land transactions was part of customary law in some regions. In 1783 Prussia enacted a General Ordinance on Mortgages and Bankruptcy, establishing land records giving public notice to land transfers and the creation of mortgages. This ordinance was the forerunner of the current Grundbuch-system, regulated by the BGB of 1900, art. 873–902 (Garro, 2004, 24).

Also in medieval England the transfer of rights in land occurred through a ceremony providing public knowledge to third parties. The transfer of a freehold estate, called feoffment, included the ceremony of livery of seisin, in which the transferor (feoffor) took the transferee (feoffee) to the concerned piece of land. There a stick, a piece of turf or a handful of soil were handed over (Garro, 2004, 28). A first attempt to establish a title system was the advent of ‘uses’, an equitable interest, recognized by the Lord Chancellor. In order to convert this equitable title into a legal one, registration of the deed of conveyance in a court of record of Westminster was required. However, this system failed. During the nineteenth century recordation initiatives were taken by the Parliament with the Land Registry Act of 1862. Among other reasons, the fact that the recordation had not been made compulsory but depended on the will of the purchaser,

Title systems and recordation of interests 193

resulted in a failure of the law. Together with a thorough simplification of land law in England a system of recordation was set up in 1925 (the Law of Property Act, the Land Registration Act). It is estimated that about 80 per cent of the land in England and Wales is recorded under this system (Garro, 2004, 34).

The early colonists in the English colonies of North America continued to practice the common law-transfer of livery of seisin. Quite soon, however, towns and states developed recordation practices which gradually supplanted the livery of seisin. The title systems in the US vary widely from state to state as concerning what has to be recorded, the way it is recorded, the legal consequences of it. Attempts to introduce more uniformity, such as the Uniform Simplification of Land Transfer Act of 1976 (USOLTA), failed (Garro, 2004, 38). Due to the archaic and incomplete character of many official recordation institutions, the private insurance sector developed title insurance, providing purchasers with additional certainty in return for a premium. The introduction of the so-called Torrens system provided an alternative to this combination of an official recording system with title insurance. The Englishman Robert Richard Torrens developed in Australia a registration system, in which the registrar acquired conclusive competences to check and validate evidence on title and to purge a title from apparent but, after checking, invalid rights and interests. Such a system, provided it was operated by able personnel, would make additional title insurance redundant. The system was introduced in Australia, the Canadian provinces Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, many African countries such as Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, Asian countries such as the United Arab Republic, Nepal, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Thailand, Turkey and Iran (Garro, 2004, 44). The Torrens system became popular in the United States during the late nineteenth century. More than 20 states passed enabling acts for a Torrens system during the period 1895–1915. Prompted by the failure of three of four title insurance companies in the state of New York during the 1930s, the New York Law Society engaged R. Powell of Columbia University in order to study an eventual introduction of the Torrens system in the state of New York. His report was highly critical about such an introduction stating that the recordation system, then prevailing in the state of New York and in 16 other states, operated at lower cost than the Torrens system. His report gave a fatal blow to the hopes that the Torrens system would be generally accepted in the United States. Many states which had adopted the system repealed the statutes (Garro, 2004, 47). The discussion about the effectiveness and efficiency of both systems still looms in legal literature, also in the law-and-economics-literature (see further 4. Registration or recording system).

194 Property law and economics

2.Title systems as a critical factor of economic development

Functional analysis of title systems, in classical legal doctrine as well as in law-and-economics, focuses on the provision of certainty in market transactions and the lowering of information costs (see further sections 3 and 4). De Soto (2000) lifted the economic function of a recordation system on the wider level of macro-economics and development economics. Recordation systems are considered as critical factors for the success of capitalist economies. While mere possession of an asset provides the holder with the immediate benefits of physical use, recordation converts the assets into genuine capital, allowing to the holder a much wider range of economic use. This conversion operates through six so-called property effects of recordation (De Soto, 2000, 49–62): 1) by recordation abstraction is made from the physical characteristics of the asset while the asset becomes represented within the conceptual universe of capital; 2) by recordation dispersed information on the potentialities of capital is integrated into one system; 3) recordation makes people accountable: individuals do not have to rely anymore on local arrangements to protect their property rights; 4) recordation makes assets fungible, i.e. assets are made able, to be fashioned to suit any transaction (for instance a single factory can be held by multiple owners); 5) recordation allows for the networking of people: by recordation assets such as buildings are legally attached to their owners which facilitates the integration into networks such as electricity provision, Internet, radio, TV and telephone cable networks; and 6) recordation protects transaction. Only the latter effect is taken into consideration by the current analysis of title systems. The larger and the poorer portion of the world population remains cut off from the benefits of the expansion of markets throughout the world because of the lack of an operational title system. The poorer urban masses within less developed countries (LDCs) dispose of a lot of entrepreneurial energy and also control many physical assets. Due to the lack of a title systems and the ensuing lack of formal protection of property rights, these poor are not able to integrate their potential into the wider network of the world market economy. They remain locked into large social pockets of economic stagnation, corruption and violence (De Soto, 2000, 18–28). Concerning the impact of De Soto’s analysis Calderon points out that the issuing of titles in Peru has increased and peaked at 400 000 in 2000, slowing down considerably since then (Calderon, 2003, 289–300). Field found that housing investment was 68 per cent higher in households with a title than in households without one (Field, 2003b, 281). Also prices increased considerably by the recordation of the property rights on housing. The Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD) and the Commission para la formalizaçion de la Propriedad Informal (COFOPRI) estimated the price effect of titling at 25